By Gordon Franz

Book Review

Robert Cornuke, The Lost Shipwreck of Paul (2003), Publisher: Global Publishing Service, Bend, OR, 232 pages.

Introduction

Mr. Robert Cornuke co-authored three books with David Halbrook and then authored a fourth book on his own in which he claimed to have used the Bible as a “treasure map” (2003: 78) in order to locate “lost” Biblical objects or places.

In the first book he co-authored, In Search of the Mountain of God: The Discovery of the Real Mt. Sinai (Cornuke and Halbrook 2000), he followed the ideas of the late Ron Wyatt and claims to have found the real Mt. Sinai at Jebel al-Lawz in Saudi Arabia (ancient Midian). Ron Wyatt was the originator of the idea and first explored the mountain with this hypothesis in mind, yet Wyatt is only mentioned in passing in Mr. Cornuke’s book (2000: 218). The Bible clearly places Mt. Sinai outside the Land of Midian (Ex. 18:27; Num. 10:29, 30). The archaeological finds observed by adventurers visiting the area were completely misidentified and misinterpreted. The claims that Mt. Sinai is Jebel al-Lawz in Saudi Arabia have been carefully examined and refuted (Franz 2000: 101-113; Standish and Standish 1999).

See also:

www.ldolphin.org/franz-sinai.html

www.ldolphin.org/franz-ellawz.html

www.ldolphin.org/cornukequestions.html

www.ldolphin.org/sinai.html

In the second book he co-authored, In Search of the Lost Mountains of Noah: The Discovery of the Real Mts. Of Ararat (Cornuke and Halbrook 2001), he examines Ed Davis’s claim to have seen Noah’s Ark while he was stationed in Iran during World War II. Mr. Cornuke concluded that Mr. Davis saw Noah’s Ark on Mt. Savalon in Iran based on the suggestion of his Iranian tour guide. Mr. Cornuke visited the country several times in order to locate the ark, but has not seen, verified, or documented, the ark on any of his trips to Iran. It seems that Mr. Cornuke has abandoned this idea and now is searching for the ark on Mount Suleiman in the Alborz Range of Iran.

See: www.noahsarksearch.com/iran.htm

In the third book he co-authored, In Search of the Lost Ark of the Covenant, (Cornuke and Halbrook 2002), he suggested that the Ark of the Covenant is located in the stone chapel of St. Mary of Zion Church in Aksum, Ethiopia. This is a revisiting of Graham Hancock’s idea in the book, The Sign and the Seal (1992). Professor Edward Ullendorff, formerly of the University of London, visited the church in 1941 and was given access to the “ark.” As an eyewitness, he reported that it was an empty wooden box! (Hiltzik 1992: 1H). The claims that the ark is in Ethiopia have been examined and refuted by Dr. Randall Price (2005: 101-115, 167-177).

Mr. Cornuke has not set forth any credible historical, geographic, archaeological or Biblical evidence for the claims he makes in his first three books when one examines them closely.

Most recently, Mr. Cornuke has developed a new idea regarding the shipwreck of the Apostle Paul. In his fourth book, The Lost Shipwreck of Paul (2003), Mr. Cornuke claims to have found the only tangible remains from the shipwreck of the Apostle Paul on Malta, six lead anchor stocks. Josh McDowell’s prominent endorsement on the dust jacket says, “The Lost Shipwreck of Paul is evidence that demands a verdict,” a play on the title of McDowell’s famous book, Evidence that Demands a Verdict. This article will examine the claims set forth in the book and will render a verdict based on the evidence.

I began my research on Malta in January 1997 in preparation for a study tour with a graduate school. Two follow-up trips were made in May 2001 and January 2005. In addition to research visits, I have amassed a large collection of books, journal articles and maps over the past few years. While on Malta, I was able to use several libraries for research. I visited the St. Thomas Bay region on three occasions and examined the two anchor stocks discussed in the book. These had been anchors that were turned over to the authorities, and displayed on the second floor of the Malta Maritime Museum in Vittoriosa along with other anchor stocks that likewise were not from controlled archaeological excavations.

Malta – A Great Place to Visit!

Malta is an island, rich in archaeological remains, fascinating history, natural beauty, and has Biblical significance. This island is a jewel of Europe and well worth a visit. A tourist can still experience the “unusual kindness” and hospitality that Paul and Luke experienced when they unexpectedly visited the island in AD 59/60 (cf. Acts 28:2 NKJV).

Examining the Evidence for the Shipwreck on the Munxar Reef

Mr. Cornuke’s investigations on the island of Malta led to the conclusion that the shipwreck occurred on the eastern end of the island of Malta, rather than the traditional site at St. Paul’s Bay on the northern side of the island. His view is that the Alexandrian grain ship containing the Apostle Paul and his traveling companion, Luke, was shipwrecked on the Munxar Reef near St. Thomas Bay on the eastern side of the island. Mr. Cornuke claims that he located local spear fishermen and divers who told him about six anchor stocks that were located near or on the Munxar Reef. Mr. Cornuke has suggested that these six anchor stocks came from the shipwreck of Paul (Acts 27:29, 40). Four of the anchor stocks were found at fifteen fathoms, or ninety feet of water (Acts 27:28), these would have been the ones the crew threw over first. The other two were found at a shallower depth and he thinks these were the anchors the sailors were pretending to put out from the prow (Acts 27:30). He identifies the “place where two seas meet” (Acts 27:41) as the Munxar Reef and the “bay with the beach” as St. Thomas Bay (Acts 27:39). He concluded that neither the sea captain, nor his crew, would have recognized the eastern shoreline of the Maltese coast.

Mr. Cornuke made four trips to Malta in order to develop this theory. On his first trip in September 2000 (2003: 26-73), he scouted out the traditional site at St. Paul’s Bay and concluded that it did not line up with the Biblical account. Then he investigated Marsaxlokk Bay and decided that it did not fit the description either. He settled on the Munxar Reef as the place where the ship foundered and St. Thomas Bay as the beach where the people came ashore.

On his second trip in September 2001 (2003: 75-130), he took a team of people that included Jean Francois La Archevec, a diver; David Laddell, a sailing specialist; Mark Phillips, his liaison with the scholarly community; Mark’s wife; and Mitch Yellen (2003: 75, 76, plate 8, bottom). On this trip, the group met Ray Ciancio, the owner of the Aqua Bubbles Diving School (2003: 77). Mr. Ciancio told the research team that two anchors had been found off the outer Munxar Reef in front of a large underwater cave. The team scuba dived to the cave and confirmed that the depth was 90 feet, or 15 fathoms.

The third trip to Malta in May of 2002 was prompted by a phone call from Mr. Ciancio claiming he located somebody who had brought up a third anchor (2003: 163-200). This time the research / film team consisted of Jim and Jay Fitzgerald, Edgar, Yvonne and Jeremy Miles, Jerry and Gail Nordskog, Bryan Boorujy, David Stotts and Darrell Scott (2003: Plate 12 top). They met Charles Grech, a (now) retired restaurant owner, who found the third anchor in front of the same underwater cave. Mr. Grech led them to a fourth anchor that might have been found off the Munxar Reef, but this was not certain. Prof. Anthony Bonanno, of the University of Malta, examined the third anchor stock in Mr. Grech’s home. The team also visited the Rescue Coordination Center of the Armed Forces of Malta and watched a computer program plot the course of a ship caught in a windstorm from Crete to Malta. Mr. Nordskog recounted his adventures and made the first official announcement of the new theory in a magazine that he published (2002: 4, 113).

A fourth trip to Malta was in November 2002 (2003: 201-220). Mr. Cornuke teamed up with Ray Ardizzone to meet Wilfred Perotta, the “grandfather of Malta divers.” Mr. Perotta was able to confirm that the fourth anchor was found off the Munxar Reef and introduced the author to a mystery man who informed him of a fifth anchor and a sixth anchor found off the Munxar Reef.

After his investigations, the author had a problem. He had no tangible proof of the anchor stocks to show the world. The first of the anchor stocks was melted down; the second, third and fourth were in private collections; and the fifth and six had been sold. According to the Maltese antiquities law, it was illegal for the private citizens to have the anchor stocks in their possession, a fear expressed by each diver/family that told their stories about the anchor stocks in his or its possession (Cornuke 2003: 108, 112, 126). A strategy, however, was devised that would get those who possessed the anchor stocks to reveal them to the public. The aid of the US ambassador to Malta, Kathy Proffitt, was enlisted to convince the President and Prime Minister of Malta to offer an amnesty to anyone who would turn over antiquities found off the Munxar Reef (2003: 221-223). The pardons were issued on September 23, 2002. This resulted in two anchor stocks being turned over to the authorities. Now the book could be written.

Thorough Research?

When I first read the book, I was disappointed to find that Mr. Cornuke does not interact with, or mention, some very important works on the subject of Paul’s shipwreck; nor are they listed in his bibliography. The classic work on this subject is James Smith’s The Voyage and Shipwreck of St. Paul. In fact, the noted New Testament and classical scholar, F. F. Bruce said this book was “an indispensable handbook to the study of this chapter [Acts 27]” (1981: 499), and elsewhere, “This work remains of unsurpassed value for its stage-by-stage annotation of the narrative of the voyage” (1995: 370, footnote 9). Yet nowhere in his book does Mr. Cornuke mention Smith’s work or even discuss the information contained therein. Nor is there any mention of George Musgrave’s, Friendly Refuge (1979), or W. Burridge’s, Seeking the Site of St. Paul’s Shipwreck (1952). There are some scholars who do not believe Paul even was shipwrecked on the island of Malta. Nowhere in Mr. Cornukes’ “Lost Shipwreck” is there an acknowledgment or even a discussion of the Dalmatia or Greek sites.

James Smith identifies the place of landing as St. Paul’s Bay; others suggest different beaches within the bay. Musgrave suggested the landing was at Qawra Point at the entrance to Salina Bay. Burridge places the shipwreck in Mellieha Bay. Those who reject the island of Malta as the place of the shipwreck point out that the Book of Acts uses the Greek word “Melite” (Acts 28:1). There were two “Melite’s” in the Roman world: Melite Africana, the modern island of Malta, and Melite Illyrica, an island in the Adriatic Sea called Mljet in Dalmatia (Meinardus 1976: 145-147). A recent suggestion for the shipwreck was the island of Cephallenia in Greece (Warnecke and Schirrmacher 1992).

Did the sea captain and crew recognize the land? (Acts 27:39)

Luke states, “When it was day, they did not recognize the land; but they observed a bay with a beach” (Acts 27:39a). The sea captain and the sailors could see the shoreline, but did not recognize the shoreline and where they were. It was only after they had gotten to land that they found out they were on the island of Malta (Acts 28:1).

Lionel Casson, one of the world’s leading experts on ancient nautical archaeology and seafaring, describes the route of the Alexandrian grain ships from Alexandria in Egypt to Rome. In a careful study of the wind patterns on the Mediterranean Sea and the account of Lucian’s Navigation that gives the account of the voyage of the grain ship Isis, he has demonstrated that the ship left Alexandria and headed in a northward direction. It went to the west of Cyprus and then along the southern coast of Asia Minor (modern day Turkey) and headed for Knidos or Rhodes. The normal route was under (south of) the island of Crete and then west toward Malta. Thus the eastern shoreline of Malta was the recognizable landmark for them to turn north and head for Syracuse, Sicily and on to Puteoli or Rome (1950: 43-51; Lucian, The Ship or the Wishes; LCL 6: 431-487).

Mr. Cornuke correctly states: “Malta itself was well visited as a hub of trade during the time of the Roman occupation and would have been known to any seasoned sailor plying the Mediterranean” (2003: 31). Any seasoned sailor coming from Alexandria would clearly recognize the eastern shoreline of Malta.

He also properly identified two of the many ancient harbors on Malta as being at Valletta and Salina Bay (2003: 32). The ancient Valletta harbor was much further inland in antiquity and is called Marsa today, and is at the foot of Corradino Hill (Bonanno 1992: 25). Roman storehouses with amphorae were discovered in this region in 1766-68 (Ashby 1915: 27-30). When Alexandrian grain ships could not make it to Rome before the sea-lanes closed for the winter, they wintered on Malta (see Acts 28:11). They would off load their grain and store them in the storehouses of Marsa (Gambin 2005). Sea captains coming from Alexandria would be very familiar with the eastern shoreline of Malta before they entered the harbor of Valletta.

The city of Melite was the only major city on Roman Malta, there were however, villas and temples scattered throughout the countryside. Today Melite lies under the modern city of Mdina / Rabat. The main harbor for Melite was Marsa, not Salina Bay (Said-Zammit 1997: 43,44,132; Said 1992: 1-22).

Diodorus Siculus, a Greek historian who lived in the First Century BC, states regarding Malta: “For off the south of Sicily three islands lie out in the sea, and each of them possesses a city and harbours which can offer safety to ships which are in stress of weather. The first one is that called Melite [Malta], which lies about eight hundred stades from Syracuse, and it possesses many harbours which offer exceptional advantages.” (Library of History 5:12:1-2; LCL 3: 129). Note his description, “many harbors.” Many includes more than just two; so where are the rest?

Knowledge of Arabic can give us a clue. The word “marsa” is the Arabic word for harbor (Busuttil 1971: 305-307). There are at least three more harbors that can be added to the list. The Marsamxett harbor within the Grand Harbor of Valletta; Marsascala Bay just north of St. Thomas Bay; and Marsaxlokk Bay in the southeast portion of Malta all would be Roman harbors. The last bay was a major Roman harbor / port that served the famous Temple of Juno on the hill above it and was also a place for ships to winter.

Any ancient Mediterranean Sea captain, or seasoned sailor on the deck of a ship anchored off the Munxar Reef, immediately would recognize the eastern shoreline of Malta with these Roman harbors and anchorages. Malta was the landmark for sailors traveling from Crete and about to turn north to Sicily. The eastern end of the island would be what they saw first and it would be a welcome sight.

There are at least four recognizable points that could be seen from the outer Munxar Reef had this been the exact spot of the shipwreck of Paul as Mr. Cornuke argues. The first was the entrance to Marsaxlokk Bay where a Roman harbor / port was, the second, the entrance to Marsascala Bay where another Roman harbor was located. The third point would be the dangerous Munxar Reef (or small islands or peninsula in the 1st century AD) that any sea captain worth his salt would recognize because of its inherent danger. The final point, and most important, was the site known today as Tas-Silg. This was a famous temple from the Punic / Roman period dedicated to one goddess known by different names by the various ethnic groups visiting the island. She was Tanit to the Phoenicians, Hera to the Greeks, Juno to the Romans, and Isis to the Egyptians (Trump 1997: 80, 81; Bonanno 1992: Plate 2 with a view of St. Thomas Bay in the background).

In preparation for my January 2005 trip to Malta I studied this important temple. It was a landmark for sailors coming from the east. Could this temple be seen from the outer Munxar Reef? On the first day I arrived in Malta, Tuesday, January 11, a fellow traveler and I went to visit the excavations. Unfortunately they were closed, but we could get a clear feel for the terrain around the excavations. Near the enclosure for the excavations was the Church of Tas-Silg, a very prominent building in the region. On Friday, January 14, we walked around the point where St. Thomas Tower is located and then along the edge of the low cliffs to St. Thomas Bay. There was no wind so the sea was flat and no waves were breaking on the Munxar Reef. On Sunday, January 16, however, a very strong windstorm hit Malta. I returned to St. Thomas Bay and walked out to the point overlooking the Munxar Reef. The waves clearly indicated the line of the Munxar Reef. After watching the waves, I turned around to observe the terrain behind me. Up the slopes of the hill the Church of Tas-Silg and the enclosure wall of the Tas-Silg excavations were clearly visible. Just to confirm the visibility from Tas-Silg, I walked along dirt paths and through fields up to the enclosure wall. As I stood on the outside of the wall, just opposite the Roman temple, I looked down and could see the waves breaking on the Munxar Reef. There was eye contact between the outer Munxar Reef and this important shrine with no apparent obstruction in the line of view. If I could see the Munxar Reef then someone at the Munxar Reef could have seen me and the elevated terrain landmarks around me such as the prominent Temple of Juno.

If the Apostle Paul’s ship was anchored near the Munxar Reef, when it was morning, the sea captain and the sailors immediately would have recognized where they were. Luke, who was on board the ship, testifies that they did not recognize where they were (Acts 27:39). Thus the Munxar Reef does not meet the Biblical criteria for the shipwreck of Paul.

Is the “Meeting of two seas” at the Munxar Reef? (Acts 27:41)

When the sea captain gave the orders for the ropes of the four anchors to be cut, Luke says they struck “a place where two seas meet” (Acts 27:41). The Greek words for “two seas meet” is transliterated, “topon dithalasson.” The meaning of these two Greek words, “two seas meet,” has been translated in the book as “place of two seas” (2003: 71), “a place where two seas meet” (2003: 217), “two seas meet” (2003: 29, 73, 194), and “a place between waters” (2003: 29).

Mr. Cornuke gives three possible meanings for this Greek phrase on page 82 of his book and footnotes it as his #16. Footnote 16 is page 148 of Joseph Thayer’s Greek-English Lexicon of the New Testament (1893). When one examines Thayer’s definition of topon dithalasson, he gives more definitions than Mr. Cornuke gives in his book. Thayer starts off by saying it means, “resembling [or forming] two seas.” Also “lying between two seas, i.e. washed by the sea on both sides … an isthmus.” If we take these omitted meanings into consideration, it opens up other possibilities on the island for the location of the shipwreck.

There have been other studies done on the Greek phrase topon dithalasson which appears only once in the Greek New Testament (Gilchrist 1996: 42-46). Professor Mario Buhagiar, of the University of Malta, cautions that this term “does not offer any real help because it can have several meanings and the way it is used in Acts 27:41, does not facilitate an interpretation. A place where two seas meet (Authorized and Revised versions) and a cross sea (Knox Version) are the normally accepted translations but any beach off a headland (Liddell and Scott) or an isthmus whose extremity is covered by the waves (Grimms and Thayer), as indeed most water channels, can qualify as the place where the boat grounded. The truth is that the Acts do not give us sufficient clues to help in the identification of the site” (Buhagiar 1997: 200).

There are other locations on the island that fit the description of the lying between two seas and an isthmus.

Is the “bay with a beach” at St. Thomas Bay? (Acts 27:39)

In introducing this passage, Mr. Cornuke remarks, “The Bible states that sailors aboard Paul’s ship, having anchored off the coast of Malta in a near hurricane, peered out at the horizon at midnight on the fourteenth night, and … observed a bay with a beach” (2003: 27). Actually, verse 39 states, “Now when it was day …” (NKJV), “And when day came …” (NASB), “And when it was day…” (KJV). It was not midnight as stated in the book. If it were at midnight, and especially during a gragale, it would be pitch black and they would not have been able to see anything.

There is a second problem with Mr. Cornuke’s identification. According to Map 3, the ship was anchored on the south side of the Munxar Reef before the ropes were cut. More than likely in the First Century AD, the sea captain would not have been able to see the low-level beach of St. Thomas Bay from where he was anchored though the elevated landmarks would have been visible and recognizable.

Geographers who study land forms are well aware that coastlines change over time. This could be a result of silting, as in the case of Marsa and the Marsascala Bay. Erosion by the sea is always going on. Seismic activity could change coastlines as well. Malta has many fault lines on or around it that could move land mass up, down or sideways. A certain depth in the sea, or elevation on land, today might not necessarily be what it was 1,000 or 2,000 years ago. Tsunamis are known in the Mediterranean Sea, and several have been recorded in the history of Malta. In 1693 a tsunami hit the island of Gozo. The water receded a mile and then returned with a vengeance (Azzopardi 2002: 60). Shifting sand moved by a tsunami could have changed the contour of the seabed.

A careful look at Map 2 with a magnifying glass reveals that the Munxar Reef is above the waterline and has what appeared to be three small islands. Unfortunately this map is not identified; nor is there a date given for when or by whom it was produced.

The D’Aleccio map of the siege of Malta in 1565 was produced and published in 1582. On that map, the Munxar Reef appears as a series of small islands or a peninsula (Ganado 1984: Plate 18).

An Internet search revealed the Boisgelin Map of Malta produced in 1805, but I have not examined this map first hand. The Munxar Reef looked like the horn of a unicorn. Geographically, it could be a peninsula or a series of small islands.

The earliest known map of Malta was produced in 1536 (Vella 1980). Map 2 must be later than this one, as are the D’Aleccio and Boisgelin maps. They tell us that at least in the 16th century there were three small islands, or a peninsula, above the Munxar Reef. The question is, what was the reef like in the First Century AD? According to the “Geological Map of the Maltese Islands” (Map 1, 1993) the cliff overlooking the Munxar Reef is made of Middle Globigerina Limestone. It is described as “a planktonic foraminifera-rich sequence of massive, white, soft carbonate mudstones locally passing into pale-grey marly mudstone.” Assuming the small islands and/or peninsula were made of the same material, over 2,000 years this soft limestone would have eroded away by the constant wave action and occasional tsunamis. If this is the case, it raises some interesting questions: Were the small islands bigger, or was it a peninsula in the First Century AD? If so, how high was the land and how far out did it go? If it were higher than the grain ship, then it would lead to serious questions as to whether the captain could see the beach at all. It might have even been impossible to cross over it by sea in order to reach the beach.

The Six Anchors (Acts 27: 28-30, 40)

Mr. Cornuke interviewed people, primarily old divers and spear fishermen, who claimed to have located four anchors on the south side of the Munxar Reef at 15 fathoms, or 90 feet of water. These interviews are the author’s prime evidence for Paul’s shipwreck. To be more precise, Mr. Cornuke located four anchor stocks, a stock being one part of a whole anchor.

Before discussing the six anchor stocks that allegedly were discovered, a description of a wooden Roman anchor is necessary. Roman anchors were made of wood and lead, as opposed to stone anchors of earlier periods. Douglas Haldane, a nautical archaeologist, has divided the wooden-anchor stocks into eight types (Haldane 1984: 1-13; 1990: 19-24, see diagram on page 21). Five of the types were used in the first century AD, Type IIIA, IIIB, IIIC, IVA and IVB (Haldane 1984: 3,13).

The Type III anchors are made up of five parts (for pictures, see Bonanno 1992: Plate 67; Cornuke 2003: Plate 7, bottom). The main part is the wooden shank, usually made of oak, which has a lead stock across the upper part. Haldane subdivides the Type III anchors into three parts based on the design of lead stock. Type IIIA is made of “solid lead with no internal junction with the shank.” Type IIIB is made of “solid lead with lead tenon through [the] shank.” Type IIIC is made of “lead with [a] wooden core” (1984: 3). This core of wood, called a “soul,” goes though the shank in order to pin the stock to the shank (Kapitan 1969-71: 51). On the bottom of the anchor are two wooden flukes, sometimes tipped with metal (usually copper and called a “tooth”), perpendicular to the anchor stock. A “collar” made of lead, sometimes called an “assembly piece,” secures the flukes to the shank (Kapitan 1969-71: 52; Cornuke 2003: Plate 6, bottom; in the picture the collar is below the anchor stock).

When an anchor is dropped into the sea, the heavy lead stock brings the anchor to the bottom of the sea. One fluke then digs into the sea bottom. The stock also keeps “the anchor cable pulling at the correct angle to the fluke” (Throckmorton 1972: 78).

Mr. Cornuke concluded from his research that the anchors from an Alexandrian grain ship “would have been huge, lead-and-wooden Roman-style anchors common on huge freighters like the one Paul sailed on” (2002: 15).

Nautical archaeologists and divers generally find only the anchor stocks and the collars and not the wooden parts because the wood rots in the sea. However, that is not always the case. Sometimes the wooden core, or “soul” still is found inside the stock. Wood can also be found in the collar (Kapitan 1969-71: 51, 53). In some cases the wood does not disintegrate. A case in point is the wooden anchor from a 2,400 year-old shipwreck off the coast of Ma’agan Mikhael in Israel (Rosloff 2003: 140-146).

Sometimes lead anchor stocks have inscriptions or symbols on them. Symbols may be of “good luck (dolphins, caduceus), or related to the sea (shells) or apotropaic (Medusa head).” Also are found “numbers, names of divinities (= names of ships), e.g. Isis, Hera, Hercules, and rarely, names of men … [that] may provide evidence for senatorial involvement in trade” (Gianfrotta 1980: 103, English abstract).

One of the reasons antiquities laws are so tough is to prevent divers from looting sunken ships and removing, forever, valuable information such as the wood which could be used to carbon date the anchor and identify the type of wood used for making anchors. Some Israeli nautical archaeologists have begun to use carbon dating to date some of their shipwrecks (Kahanov and Royal 2001: 257; Nor 2002-2003: 15-17; 2004: 23). Archaeologists also work to maintain any inscriptional evidence on the anchor stock.

For a brief survey of the recent developments in the maritime heritage of Malta, see Bonanno 1995: 105-110.

The first anchor (#1) described in Mr. Cornuke’s book was found by Tony Micallef-Borg and Ray Ciancio in front of a big cave in the outer Munxar Reef at about 90 feet below the surface (2003: 101-105). When it was discovered in the early 1970’s, it was only half an anchor that was either “pulled apart like a piece of taffy” (2003: 121) or sawn in half with a hacksaw (2003: 231, footnote 18), depending on which eyewitness is most reliable. The recollection is that it was three or four feet long, with a large section cut off (2003: 102). The discoverers melted it down for lead weights not knowing its historical and archaeological value. One diver, Oliver Navarro, had two small weights with “MT” stamped on them for Tony Micallef-Borg. (Actually “MT” is the reverse image of Tony’s initials, see Plate 6, top). There is a drawing of the anchor at the top of Plate 7.

Unfortunately, #1 was melted down. If it had been found in a controlled archaeological excavation and it contained an inscription, it would have been helpful in identifying the ship or its date.

In a reconstruction of how the anchor stock was ripped apart, the author surmises that this was the first anchor thrown from the Apostle Paul’s ship and then “ravaged by the reef and the waves” (2003: 122, 123). The problem with this scenario is that a fluke goes into the seabed where it would serve to slow down the ship, not the anchor stock. If anything had been torn apart like taffy it would have been the collar, not the anchor stock, assuming the wooden fluke did not break first. More than likely, the anchor stock was sawn in half by means of a hacksaw by some unknown person in modern times..

The second anchor (#2) was also found in the early 70’s and was a whole anchor stock found near anchor #1 (2003: 105-110). It was brought to shore by Tony Micallef-Borg, Ray Ciancio, Joe Navarro and David Inglott and taken to Cresta Quay (Cornuke 2003: 105, 106). It eventually came to rest in the courtyard of Tony Micallef-Borg’s villa.

“Tony’s anchor” (2003: 125) is described by different people as a “large anchor stock” (2003: 106), a “huge anchor” (2003: 114), as a “large slab of lead” (2003: 126), and a “massive Roman anchor stock” (2003: 126). Unfortunately, unlike anchor stocks #1, #3, and #4, there are no measurements given in the book for this one. The only size indicators are the adjectives “large”, “huge”, and “massive.”

The reader viewing the photographs of anchors #2 and #3 on Plate 5 might get the impression that anchor #2 (bottom) was much larger than anchor #3 (top). The bottom picture was taken with the anchor on a bed sheet with nothing to indicate the actual size. Anchor #3 has three men squatting behind the anchor to give some perspective of size. The impression the reader would get is that anchor #2 is almost twice the size of anchor #3. If these anchors were published in a proper excavation report both anchors would have the same scale in front of them and the photograph of each anchor would be published to the same scale. It then would be seen that anchor #2 is considerably smaller than anchor #3.

On Friday, January 14, 2005 and Monday, January 17, 2005 I visited the second floor of the Malta Maritime Museum in Vittoriosa. “Tony’s anchor” was tagged “NMA Unp. #7/2 Q’mangia 19.11.2002.” This anchor stock came from the village of Q’mangia and was handed over to the museum on November 19, 2002, only four days before the amnesty expired (2003: 223).

The anchor stock was one of the smallest on display, measuring about 3 feet, 8 inches in length. Large Alexandrian grain ships would have had for the stern much larger anchors than this one. The author’s lack of quantifiable measurements regarding the anchor stock keeps the reader uninformed about its actual size. This anchor stock is a lead toothpick compared to “huge, lead-and-wooden Roman-style anchors” that Mr. Cornuke surmised would be on the ship (Cornuke 2002: 15).

The “Museum Archaeological Report” for 1963 describes an anchor stock found off the coast of Malta. It was an “enormous Roman anchor stock lying on the sea bed 120 feet below the surface 300 yards off Qawra Point … its dimensions, 13 feet 6 inches long, were confirmed. … On the same occasion part of the same or another anchor, a collar of lead 84 cms. long, was retrieved from 25 feet away from the stock” (MAR 1963: 7; Fig. 6; Plate 3). It weighed 2,500 kg, which is two and a half metric tons! (Guillaumier 1992: 88). This anchor stock is the largest anchor stock ever found in the Mediterranean Sea and most likely came from an Alexandrian grain ship. It is in storage in the National Archaeological Museum in Valletta. A picture of it can be seen in Bonanno 1992: 158, plate 66.

This anchor would be a Type IIIC anchor according to Haldane’s classification. He dates this type of stock from the second half of the second century BC to the middle of the first century AD based on two secure archaeological contexts (1984: 8).

If this anchor stock had been recovered in a controlled archaeological excavation there might have been some wood found in the “soul.” If so, this could have been used for carbon dating and given us a clearer date for the casting of the anchor stock.

According to Mr. Cornuke, on two occasions Professor Anthony Bonanno was shown a video of this anchor stock. The first was during dinner with Mr. Cornuke, Dr. Phillips and his wife on their second trip to Malta. Professor Bonanno was shown it on the screen of a tiny video (2003: 128). The professor concluded, “Anchor stocks such as the one you are showing me in this video were used from approximately 100 B.C. to 100 A.D. It could have come from any period within that range” (2003: 129). The video was again shown to him on Mr. Cornuke’s third trip to Malta. Again, it was viewed on the screen of a small video camera. The professor states, “From what I can tell from these videos – again without the benefit of physical examination – these other two anchors also appear to be typical Roman anchor stocks, appropriate to the era of St. Paul’s shipwreck in Malta” (2003: 184). Professor Bonanno qualifies his observation because he has not physically examined the anchor stock in person. It is difficult to evaluate an archaeological find on a small video screen. There is no mention in the book of the professor making a “physical examination” of this anchor stock in the Nautical Museum.

The third anchor (#3) was found by Charles Grech and Tony Micallef-Borg on Feb. 10, 1972, the feast of St. Paul and Charles’ 33rd birthday. It was found in front of the big cave at the Munxar Reef and brought up with the help of Tony Micallef-Borg soon after he had found the first two anchors. Anchor #3 measured “a little over five feet long” (2003: 164). It was taken to Charles’ house where it resided until he turned it over to the national museum. The tag on the anchor says, “NMA unp # 7/1 Naxxar.” A picture of it can be seen at the top of Plate 5. From my observation of this anchor, it had the lead tenon through the shank, thus making it a Type IIIB anchor. Haldane dates this type anchor stock from the mid-second-century BC to the mid-first century BC. Recently, however, Roman legionary anchors were discovered that date to about AD 70 (Haldane 1984: 8).

Professor Anthony Bonanno examined this anchor and very cautiously said, “It could have belonged to a cargo ship, possibly a grain cargo ship, and possibly one from Alexandria” (2003: 183, emphasis by the reviewer). He went on to conjecture, “This anchor stock would fit very well within the era of St. Paul” (2003: 184).

The fourth anchor (#4) was found by “Mario” (a pseudonym) in the late 60’s (2003: 176, 204) and was over 5 feet long (2003: 171). It was taken to “Mario’s” house where it resides in his courtyard. A picture of it can be seen at the bottom of Plate 6. One can observe the lead tenon, making this a Type IIIB anchor as well.

His widow was not sure whether it was found off the Munxar Reef or Camino, the island between Malta and Gozo (2003: 178). Wilfred Perotta, however, was able to confirm that the anchor was found off the Munxar Reef (2003: 204).

Anchor #4 supposedly is in a private collection and the holders are having “meaningful dialogue” with the authorities (Cornuke 2003: 221). “Meaningful dialogue” is an interesting description as the antiquity laws are clear; all ancient artifacts must be turned over to the proper authorities. A general amnesty was issued and the deadline passed.

The other two anchors (#5 and #6), were found by a mystery diver who did not want his identity revealed (2003: 212). In an account that reads like a cloak and dagger mystery, the author relates his conversation with this individual (2003: 210-215). The diver claims he found the two anchors in 1994 in front of the “Munxar Pass” in about 10 meters (ca. 33 feet) of water (2003: 213). The mystery man claims to have sold them (2003: 214). The whereabouts of these two anchors are unknown. There is no description of these anchors so the type cannot be determined.

Mr. Cornuke implies that these are the anchors the sailors on the Alexandrian grain ship were trying to let down right before they were shipwrecked (2003: 208-210, see Acts 27:29,30).

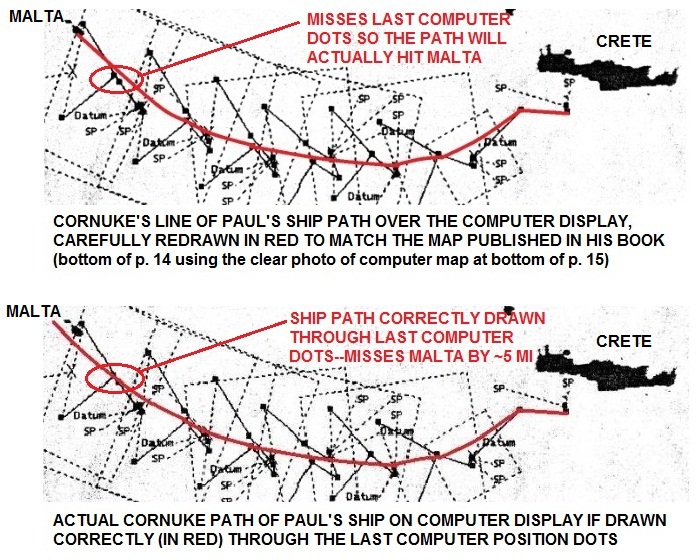

Computer model

On his third trip to Malta, Mr. Cornuke gained access to a sophisticated computer at the Rescue Coordination Center of the Armed Forces of Malta with hope that it would “objectively speak to us across the millennia and trace the, until now, uncertain path of the biblical event of Paul’s journey from Crete to Malta” (2003:184). Computer models are only as good as the information put into the program.

The information put into the computer program included: (1) the “general parameters of a grain freighter,” (2) the type of wood from the wooden hull, (3) the “veering characteristics of a northeaster,” (4) the “leeway of time,” and (5) the currents during the fall season for that part of the Mediterranean Sea (2003: 188). Unfortunately, the specific information that was put into the computer was not given in the book, perhaps to maintain a less technical approach for a popular-level book. Researchers, however, who would like to follow up on this exercise, would need the specific information.

It should be pointed out that “the precise appearance of great grain ships like those mentioned in the Book of Acts and the writings of Lucian” are unknown (Fitzgerald 1990: 31). Was it a two-mast or a three-mast grain ship? How much did it actually weigh? How did the drag of the windsock, or sea anchors affect the speed and direction of the ship (Acts 27:17 NASB)? What time did they leave Fair Haven on Crete? Was it morning or mid-day? Exactly what time did the wind begin to blow? These are unknown variables that cannot be put into the computer calculations and would affect the outcome of the computer model. Of course, the biggest unknown factor would be the sovereign Hand of God controlling the speed and direction of the wind.

It is not accurate to conclude that “the computer program confirmed that the ship must have had [sic] come from the south and that its drift had completely eliminated St. Paul’s Bay and other bays closely associated with it as the possible landing site” (Cornuke 2003: 192). To use a baseball analogy, the computer model can put you into the ballpark (Malta in fourteen days), but it cannot guarantee a hit, much less a home run (St. Thomas Bay)!

Syrtis – Sandy beach or Shallow Bays with Sand bar?

The reader should be cautious with some of the geographical positions taken in the book that are, at worst, not accurate and that at best, needing more discussion. A case in point is that of the Syrtis mentioned in Acts 27:17. The author identifies it as “an inescapable vast wasteland of sun-scorched sand where they would certainly suffer a slow, waterless death” (Cornuke 2003: 42). According to the book, this sand was on the northern coast of Africa (2003: 190 and map 1). Unfortunately we have no idea where this idea came from because it is not footnoted or documented.

In actuality, the Syrtis was not dry desert but two bodies of water, the “name of two dangerous, shallow gulfs off the coast of North Africa” (Olson 1992:4: 286).

Strabo, a Greek geographer, describes the location and dimensions of the Greater and Lesser Syrtis in his Geography (2:5:20; LCL 1: 473,745). Elsewhere he describes these two bodies of water in these terms: “The difficulty with both [the Greater] Syrtis and the Little Syrtis is that in many places their deep waters contain shallows, and the result is, at the ebb and the flow of the tides, that sailors sometimes fall into the shallows and stick there, and that the safe escape of a boat is rare. On this account sailors keep at a distance when voyaging along the coast, taking precautions not to be caught off their guard and driven by winds into these gulfs” (Geography 17:3:20; LCL 8: 197). No wonder the sailors on the ship the Apostle Paul was on were in fear of the Syrtis, there was no escape (Acts 27:17).

Dio Chrysostom describes the Syrtis in these terms: “The Syrtis is an arm of the Mediterranean extending far inland, a three days’ voyage, they say, for a boat unhindered in its course. But for those who have once sailed into it find egress impossible; for shoals, cross-currents, and long sand-bars extending a great distance out make the sea utterly impassable or troublesome. For the bed of the sea in these parts is not clean, but as the bottom is porous and sandy it lets the sea seep in, there being no solidity to it. This, I presume, explains the existence there of the great sand-bars and dunes, which remind one of the similar condition created inland by the winds, though here, of course, it is due to the surf” (Discourse 5:8-10; LCL I: 239).

Strabo was a geographer from Pontus who lived at the end of the First Century BC and beginning of the First Century AD. Dio Chrysostom was a rhetorician and traveler who lived about AD 40 – ca. AD 120. Both would be considered near contemporaries with Luke and the Book of Acts. Luke was sandwiched between these two and his understanding of the Syrtis would have been the same as Strabos’ and Dio Chrysostoms’ understanding. Today, the Greater Syrtis is the Gulf of Sirte off the coast of Libya. The Lesser Syrtis is the Gulf of Gabes off the coast of Tunisia (Talbert 2000: I: 552-557, maps 1, 35, 37).

The Syrtis is two bodies of water in the Mediterranean Sea, and not a “vast wasteland of sun-scorched sand” on the sandy beaches of North Africa.

Rendering a Verdict

Josh McDowell gives a prominent endorsement on the dust jacket of this book, “The Lost Shipwreck of Paul is evidence that demands a verdict.” If the case of the six anchor stocks were brought before a court, how would an impartial jury reason the case as they evaluate the evidence and render a verdict?

The first bit of evidence to be examined is the clear statement of the Book of Acts that the captain and his crew did not recognize the land when it became light (Acts 27:39). If the ship anchored off the Munxar Reef, the captain and crew would have recognized the eastern shore of Malta because it was a familiar landmark for them. Mr. Cornuke’s theory goes contrary to the clear statement in the Book of Acts.

The next issue to consider is the “topon dithalasson,” the place where two seas meet (Acts 27:41). We would concur with Prof. Buhagiar that the evidence here is inconclusive and that other sites on Malta are just as likely.

The third issue to consider is the “bay with a beach” (Acts 27:39). When confronted with the evidence from the maps of Malta from the last 500 years, we can recognize that more than likely the ship’s captain would not have seen the low-lying beach of St. Thomas’s Bay because the Munxar Reef was actually a series of small islands or a peninsula in the First Century AD which would have blocked their view of the beach. Yet the Bible says the crew of Paul’s shipwreck saw a “bay with a beach.”

The last bit of evidence is the anchors. There are only two actual anchor stocks to consider, anchor stock #2 and anchor stock #3. Anchor stocks #1, #4, #5, #6 cannot be produced and examined. Anchor stock #1 was melted down, #4 is in a private collection, and #5 and #6 were sold on the antiquities market.

One could conclude that anchor stock #2 could not belong to a large Alexandrian grain ship because it was too small to be used as an anchor in the stern of the ship. The only anchor stock that might possibly be from a grain ship is #3.

The “case” record here shows that credible historical, archaeological, geographic, and Biblical evidence contradict the claim that the anchors found off the Munxar Reef were from Paul’s shipwreck and that the landing took place at St. Thomas Bay. The evidence demands a dismissal of this case!

Bibliography

Ashby, Thomas

1915 Roman Malta. Journal of Roman Studies 5: 23-80.

Azzopardi, Anton

2002 A New Geography of the Maltese Islands. Second Edition. Valletta, Malta: Progress Press.

Bonanno, Anthony

1992 Roman Malta. The Archaeological Heritage of the Maltese Islands. Formia, Malta: Giuseppe Castelli and Charles Cini / Bank of Valletta.

1995 Underwater Archaeology: A New Turning-Point in Maltese Archaeology. Hyphen. A Journal of Melitensia and the Humanities. 7: 105-110.

Bruce, F. F.

1981 The Book of the Acts (NICNT). Grand Rapids: Eerdmans.

1995 Paul. Apostle of the Heart Set Free. Grand Rapids: Eerdmans.

Buhagiar, Mario

1997 The St. Paul Shipwreck Controversy. An Assessment of the Source Material. Pp. 181-213 in Proceedings of History Week 1993. Edited by K. Sciberras. Malta: Malta Historical Society.

Burridge, W.

1952 Seeking the Site of St. Paul’s Shipwreck. Valletta, Malta: Progress Press.

Busuttil, J.

1971 Maltese Harbours in Antiquity. Melita Historica 4: 305-307.

Casson, Lionel

1950 The Isis and Her Voyage. Transactions and Proceedings of the American Philological Association 81: 43-56.

Cornuke, Robert

2002 Paul’s “Miracle on Malta.” Personal Update (April) 14-16.

2003 The Lost Shipwreck of Paul. Bend, OR: Global Publishing Services.

Cornuke, Robert, and Halbrook, David

2000 In Search of the Mountain of God. The Discovery of the Real Mt. Sinai. Nashville, TN: Broadman and Holman.

2001 In Search of the Lost Mountains of Noah. The Discovery of the Real Mts. Of Ararat. Nashville, TN: Broadman and Holman.

2002 In Search of the Lost Ark of the Covenant. Nashville, TN: Broadman and Holman.

Dio Chrysostom

1971 Discourses I – IX. Vol. 1. Translated by J. W. Cohoon. Cambridge, MA: Harvard University. Loeb Classical Library.

Diodorus Siculus

1993 The Library of History. Books IV.59-VIII. Vol. 3. Translated by C. Oldfather. Cambridge, MA: Harvard University. Loeb Classical Library.

Fitzgerald, Michael

1990 The Ship of Saint Paul. Comparative Archaeology. Biblical Archaeologist 53/1: 31-39.

Franz, Gordon

2000 Is Mount Sinai in Saudi Arabia? Bible and Spade 13/4: 101-113.

Gambin, Timothy

2005 Ports and Port Structures for Ancient Malta. Forthcoming.

Ganado, Albert

1984 Matteo Perez d’Aleccio’s Engraving of the Siege of Malta 1565. Pp. 125-161 in Proceedings of History Week 1983. Malta: Malta Historical Society.

Gianfrotta, Piero

1980 Ancore “Romane”. Nuovi Materiali Per Lo Studio Dei Traffici Marittime. Pp. 103-116 in The Seaborne Commerce of Ancient Rome: Studies in Archaeology and History. Edited by J. H. D’Arms and E. C. Kopff. Rome: American Academy in Rome.

Gilchrist, J. M.

1996 The Historicity of Paul’s Shipwreck. Journal for the Study of the New Testament 61: 29-51.

Guillaumier, Paul

1992 New Perspectives on the Historicity of St. Paul’s Shipwreck on Melite. Pp. 53-97 in St. Paul in Malta. Edited by M. Gaiea and J. Ciario. Malta: Veritas.

Haldane, Douglas

1984 The Wooden Anchor. Unpublished MA thesis. Texas A & M University. College Station, TX.

1990 Anchors in Antiquity. Biblical Archaeologist 53/1: 19-24.

Hancock, Graham

1992 The Sign and the Seal. The Quest for the Lost Ark of the Covenant. New York: Crown.

Hiltzik, Michael

1992 Does Trail to Ark of Covenant End Behind Aksum Curtain? A British Author Believes the Long-Lost Religious Object May Actually Be Inside a Stone Chapel in Ethiopia. Los Angeles Times June 9, page 1H.

Kahanov, Ya’acov, and Royal, Jeffery G.

2001 Analysis of Hull Remains of the Dor D Vessel, Tantura Lagood, Israel. The International Journal of Nautical Archaeology 30: 257-265.

Kapitan, Gerhard

1969-71 Ancient Anchors and Lead Plummets. Pp. 51-61 in Sefunim (Bulletin). Haifa: Israel Maritime League.

Lucian

1999 Lucian. Vol. 6. Translated by K. Kilburn. Cambridge, MA: Harvard University. Loeb Classical Library.

M. A. R.

1963 Underwater Archaeology. Report on the Working of the Museum Department. Malta: Department of Information.

Meinardus, Otto

1976 St. Paul Shipwrecked in Dalmatia. Biblical Archaeologist 39/4: 145-147.

Musgrave, George

1979 Friendly Refuge. Heathfield, Sussex. Heathfield.

Nor, Hades

2002-2003 The Dor (Tantura) 2001/1 Shipwreck. A Preliminary Report. R. I. M. S. News. Report 29: 15-17.

2004 Dor 2001/1: Excavation Report, Second Season. R. I. M. S. News. Report 30: 22,23.

Nordskog, Gerald

2002 One Memorable Ride. Powerboat 34/10 (October) 4, 113.

Olson, Mark

1992 Syrtis. P. 286 in Anchor Bible Dictionary. Vol. 6. Edited by D. Freedman. New York: Doubleday.

Price, Randall

2005 Searching for the Ark of the Covenant. Eugene, OR: Harvest House.

Rosloff, Jay

2003 The Anchor. Pp. 140-146 in The Ma’agan Mikhael Ship. The

Recovery of a 2400-Year-Old Merchantman. Vol. 1. Edited by E. Black. Jerusalem and Haifa: Israel Exploration Society and University of Haifa.

Said, George

1992 Paola: Another Punico-Roman Settlement? Hyphen 7/1: 1-22.

Said-Zammit, George

1997 Population, Land Use and Settlement on Punic Malta. A Contextual Analysis of the Burial Evidence. Oxford: Archaeopress. BAR International Series 682.

Smith, James

1978 The Voyage and Shipwreck of St. Paul. Grand Rapids: Baker. Reprint from the 1880 edition.

Standish, Russell, and Standish, Colin

1999 Holy Relics or Revelation. Recent Astonishing Archaeological Claims Evaluated. Rapidan, VA: Hartland.

Strabo

1989 The Geography of Strabo. Vol. 1. Translated by H. L. Jones. Cambridge, MA: Harvard University. Loeb Classical Library.

1982 The Geography of Strabo. Vol. 8. Translated by H. L. Jones. Cambridge, MA: Harvard University. Loeb Classical Library.

Thayer, Joseph

1893 A Greek-English Lexicon of the New Testament. New York: Harper and Brothers.

Talbert, Richard, ed.

2000 Barrington Atlas of the Greek and Roman World. 2 volumes and atlas. Princeton, NJ: Princeton University.

Throckmorton, Peter

1972 Romans on the Sea. Pp. 66-78 in A History of Seafaring Based on Underwater Archaeology. Edited by G. Bass. New York: Walker.

1987 The Sea Remembers. Shipwrecks and Archaeology. New York: Weidenfeld and Nicolson.

Trump, David

1997 Malta: An Archaeological Guide. Valetta, Malta: Progress.

Vella, Horatio C. R.

1980 The Earliest Description of Malta (Lyons 1536) by Jean Quintin d’Autun. Sliema, Malta: DeBono Enterpriese.

Warnecke, Heinz, and Schirrmacher, Thomas

1992 War Paulus wirklick auf Malta? Neuhausen-Stuttgart: Hanssler-Verlag.

Recent Comments